YOMI BRAESTER'S PAPER ON "WHOSE EYES"

Yomi Braester's lecture on this paper

Yomi Braester is a professor, Byron W. and Alice L. Lockwood Professor in the Humanities, University of Washington.

His research focuses on literary and visual practices, with emphasis on modern China and Taiwan—in architecture, advertisement, screen media, and stage arts. I inquire how texts and images form and manipulate our perception of space and history. I am the founding director of the UW Summer Program in Chinese Film History and Criticism at the Beijing Film Academy and have served as the president of the Association for Chinese and Comparative Literature.

More about Yomi Braester:

More about "Whose Eyes":

[excerpts]

The City as Found Footage: The Reassemblage of Chinese Urban Space

Published in Global Cinematic Cities: New Landscapes of Film and Media, edited by Johan Andersson and Lawrence Webb (Wallflower, 2016), 157‒177.

The urban environment of the twenty-first century is to a large extent defined by two forms of the moving image: surveillance videos and found footage. By virtue of their presence, security cameras identify public space as subject to regulation. These cameras, often forming large networks, capture the city’s temporal flow and trace citizens’ movement of people through space. The ubiquity of surveillance videos is an exponent of the increased data gathering and production of information. Found footage is also a symptom of a shift of a larger scale, toward a comprehensive sharing of content produced by individual citizens. In its broader sense, found footage includes any images made for occasions other than the ones in which it is used. Now the majority of these images are generated by private devices — most prominently smartphones — and subsequently disseminated and circulated on the Internet, especially through peer-to-peer platforms and social media.

At first glance, surveillance videos and found footage seem to stand on opposite ends of the spectrum that marks our relation as visual subjects to the spaces we inhabit. Surveillance videos are an extreme manifestation of spatial control, in which sites function as theatrical sets for a spectacle regimented by security cameras. Built environment is reduced to scaffolding for events that are primarily visual. The contemporary city in particular is immersed in a system of images that renders everything visible, practically everywhere and always. Found footage, on the other hand, is the outcome of loss of control. Whatever intent may have lied behind its initial production, found footage is at the mercy of its finder. The images are appropriated and reinterpreted. Even insofar as found footage retains its reference to the time and place of recording, its indexical value is attenuated, compromised by its new use. Taken out of the spatial and temporal context of its production, found footage does not uphold the primacy of vision. It denotes the arbitrary repurposing of images, the discarded gaze, the relinquishing of visual agency.

Yet surveillance videos and found footage complement each other, creating a new urban media ecology. On the one hand, surveillance videos are less controlling than they might first seem. Surveillance studies stress how interconnected cameras compromise citizens’ privacy, yet I argue that such systemic analysis replicates the imagined viewpoint of network controllers and ignores the true effect of surveillance videos.[ii] In practice, even though we may imagine ourselves watched by concealed cameras and hovering aircraft, very few have direct access to the resulting images. The popular imagination is based on those clips leaked to the press and uploaded to sites such as YouTube. Notwithstanding the real threat to human rights posed by security cameras (as well as the benefit to public safety), surveillance videos enter public circulation in a form already removed from their initial intended use. At the phenomenological level, surveillance videos are no different from found footage.

On the other hand, found footage accrues added intentionality once it is appropriated and reinterpreted. Indeed, my use of ‘found footage’ is meant as a nod toward a number of practices associated with the term, which suggest an auteurial agency behind the use of readymade images. As a form of avant-garde cinema, found footage films (also known as collage or compilation films) resuscitate the authority of the image by offering ‘a radical disassociation of content and form that becomes reconstructed, reconfigured’ (Verrone 2012: 168). The collage alludes to the vulnerability of the image and at the same time invokes the possibility of recovery through the artist’s actions. Moreover, the reuse of found footage accentuates the value of fragments as the source of alternative narratives.

Reprocessing media fragments is arguably a sign of our times, due to the ease of digital reproduction, resampling, and redistribution. The large amount of clips available on sites such as YouTube brings to an extreme the ability to reassemble found footage. For Andreas Treske, online video is ‘reassembled in new contexts, levels, affordances, customizations and personalisations’ (Treske 2014:22). Yet whereas Treske thinks of video reassemblage in terms of reshuffling and material modification, the reassemblage to which I refer here consists mostly (at least in the hands of lay netizens) of recycling the same images in other media and new urban ecologies. (Furthermore, although I place reassemblage in the context of social critique and affective virality, I use the term in a rather narrow sense, skirting the implications of Deleuzian assemblage theory.)

As the repurposing of found footage, reassemblage often amounts to a rearrangement of perceived reality. The logic of reassemblage renders the profilmic irrelevant and redefines indexicality as reference to the chain of recycled images. This emphasis on the medium does not, however, amount to doing away with the signified, as in the semantics of the simulacrum. Rather, reassemblage shifts the economy of signification from the material to the visual medium as the subject of discourse. Jaimie Baron (2014) notes the historiographical crisis at the foundation of reusing documentary film fragments, which requires a recognition that our use of found footage partakes in creating the event at hand. Found footage amounts to a fluid archive; its incorporation into other films, as the case of Forrest Gump (1994, Robert Zemeckis) demonstrates, both lends credibility to the new images and adds a playful tone. By dint of referring both to its time of production and to the occasion of its reuse, found footage points to the multilayered significance of the image.

The reconfiguration of visual representation is in turn followed by a shift of auteurial agency and a modification in the role of the citizen in reimagining public space — both material (architectural) and figurative (social). The confluence of surveillance videos and found footage blurs the boundaries between the individual and public spheres, between spontaneous and designed images, and between material and virtual spaces. As a result, built environment becomes a visual ecosystem that produces, trashes, and recycles images. The city, in turn, functions both as a watching eye and as a visual objet trouvé, at the same time.

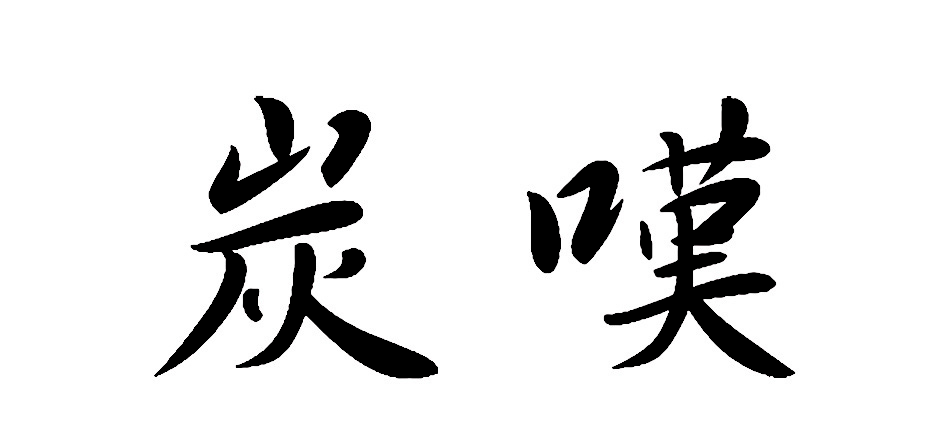

In this chapter I examine the contemporary urban ecology of the image in the People’s Republic of China through specific cases that lie on the borderline between surveillance video and found footage. They include self-made videos and selfies in Beijing’s business district of Sanlitun, the video of the death of Wang Yue, Tan Tan’s video art ‘Shui de yanjing’ (Whose eyes, 2011), Li Juchuan’s video art ‘Sharen guocheng jin qi miaozhong’ (Murdering six people in seven seconds, 2008), and Ai Weiwei’s ‘WeiweiCam’ (2012). These cases vary widely: from a sex scandal to incidents of brutality and crime, from clips circulating widely on the Internet to video art viewed by few. Yet together they outline a discourse on the use of screens and cameras in public space.

The reality that is not one

The issues around mediatisation of public space are made explicit in Tan Tan’s video art ‘Whose Eyes’ of 2011. The 15’30’ artwork combines images from security cameras — some found footage, some staged by the artist. They present violent events and the callous reaction of bystanders. Like the discourse around the Incident of Little Yueyue, ‘Whose Eyes’ focuses on the deterioration of collective moral standards. Yet as a video artwork, Tan Tan’s piece foregrounds more explicitly the visual properties of surveillance videos and their effect on perceptions of public space. The direct referential value of the moving image gives way to a mediatised temporal and spatial indexicality that challenges the ethical efficacy of reassemblage.

The video artwork consists of images all of which seem to originate from security cameras. Often the 4:3 aspect ratio screen is split into four black-and-white video channels, much like feed from cameras sending their real-time signal to a control center.[i] The incidents featured in ‘Whose Eyes’ are four cases that drew public attention after appearing on the Internet. The first took place in Guizhou, where a man entered a bank, mugged a woman, shot her, and left the place unhindered. She was left to bleed to death for seven minutes while witnesses stood by. The second incident happened in Taizhou, where an old woman was run over by a car. As in similar cases, the driver would not risk the liability of taking care of hospital bills. He therefore reversed the car twice, rolling over the body four more times and thereby ascertaining the victim’s death. After the car left, passersby did not stop to tend to the woman. The third incident involved a bus driver in Wuhan, who instructed a passenger to add a coin for the bus fare. In response, the passenger hit the driver repeatedly. The twenty-eight bus passengers did nothing to stop the violence; instead, they demanded to be let off the bus. The fourth incident occurred in the province of Guangdong, as two men robbed a grocery store owner. A knife scuffle ensued, during which the owner was stabbed and sank to the ground. Two customers entered the store separately, but each left without helping the dying man (Anon. n.d.). The four incidents cited in ‘Whose Eyes’ represent the pervasive violence and unconcern in contemporary society.

The video artwork is a piece of social criticism. Tan Tan introduces it as follows:

"The film combines videos of real events and shots of similar life scenes, producing four ‘fake surveillance video recordings’. Interweaving reality and reality has created a contiguity of false images of life. Is our life truly normal? Are we truly normal? The four real cases took place in public space, but no one intervened, as if no one saw the scene of crime. [In the video artwork] one can only hear, in disorderly and intermittent fashion, the sounds of news commentary on the incidents. It is as if we understand the facts, but we can only perceive them in retrospect while living in darkness. Is it really that no one’s eyes can see? " (Tan 2011a).

The artist protests the absence of collective ethics, manifested in the purported ‘normalcy’ of violent incidents and the public’s lack of response. In referring to ‘us’, possibly conflating society at large and the audience of her artwork, Tan Tan questions whether the viewers of ‘Whose Eyes’ fare any better — even though the viewers may be scandalised, they remain passive onlookers. Netizens watching clips such as that documenting Wang Yue’s death believe themselves to be responsible citizens, yet ‘Whose Eyes’ shows such self-congratulatory attitude toward the consumption of found footage to be groundless.

Tan Tan also draws attention to the role of the video clips in conveying the incidents in ‘disorderly and intermittent’ media snippets, which imitate our partial understanding of social conditions. We fail to see reality, because we are unequipped to deal with visual evidence. Tan Tan does not denounce mediatised images as less real. Rather, the task for the viewer of ‘Whose Eyes’ is to learn to distinguish between the interwoven ‘reality and reality’, two kinds of images both of which have equal indexical value.[ii] As a comment on the condition of visuality in the twenty-first century, and in particular the relation between the media consumer and the moving image, ‘Whose Eyes’ shows our inability as viewers to differentiate between staged and found footage is the result of a moral handicap as much as a visual incapacity. At the mimetic level, found and staged footage are indistinguishable from each other, yet found footage carries a different ethical value.

The found footage in the Uniqlo incident and the Incident of Little Yueyue may be said to always find its addressee: it is reassembled time and again, each transformation bringing it to new audiences and making additional impact. By contrast, the found footage in ‘Whose Eyes’ — even when restored into context by Tan Tan — seems to be never truly found out and enter the viewer’s consciousness. ‘Whose Eyes’ exposes social insensitivity — not by separating mediatised images from the profilmic, but by showing such distinction to be untenable. By creating ‘a contiguity of false images of life’, the artist enhances the confusion between various mediatised forms. Reassemblage does not rescue the image but rather accentuates the inherent indexical crisis in found footage.

Tan Tan is well aware of her intervention in the mediascape. She places her work in the context of other video art — from Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren to her Chinese contemporaries — and further elaborates:

"The narrative in my ‘Whose Eyes’ reconstructs the result of recording…. what happens in each shot has truly taken place, each has its temporal flow and plot. But the interweaving of reality and reality creates a contiguity of false images of life…. One may say that experimental films that contain narrative elements often don’t aim at telling any story, only at producing ‘illusion’ ."(Tan 2011b).

In other words, Tan Tan takes narrative incoherence, a defining characteristic of experimental film, and turns it into a reflection of the citizens’ visual and social dysfunction. The narratively muddled images in ‘Whose Eyes’, in which the ‘reality’ of the found footage and the ‘reality’ of the staged videos become indistinguishable from each other, becomes a metaphor for the challenges posed by a mediatised environment.

‘Whose Eyes’ creates a disruption in the media ecology that otherwise takes for granted the reassemblage of found footage. Where the Uniqlo selfies and Incident of Little Yueyue rely on bandying the image around without change, Tan Tan introduces subtle but significant modifications. She uses low-resolution images, delays the sound track, and displays simultaneously multiple Time Code Reading signals. Tan Tan’s artwork reveals the perceptual dissociation that lies at the foundation of reassemblage. In presenting even her staged scenes as found footage, Tan Tan shows the need for critical viewing. ‘Whose Eyes’ stresses the danger in confounding found footage and the profilmic, a confusion that might result in viewing it the same way that one watches reality TV.